Why lone software projects fail

I have an awful lot of failed software projects. Most programmers do. It comes with the territory.

Most of the failures have been the result of running out of steam one way or another. Your early enthusiasm slowly wanes until the mere thought of carrying on makes you feel a little sick.

It is easy to forget that programming is an intensely psychological activity. Your attitude is central to the success or otherwise of your project.

Feature Creep

In my experience, I fail most often when I don’t maintain feature discipline. At the beginning of a project, you define the requirements for the project. The minimal set of features that are useful. You then start implementing those requirements. If those requirements stay basically the same whilst the project is being developed, you’ve greatly improved your chances of delivering the project successfully. If however during the development stage new requirements are being added to the project, then your chances of success greatly diminish.

Requirements are likely to change, in the beginning of a project you’ll be coming up with loads of new ideas. How can you control this process so it doesn’t knock the project off course?

Gather Requirements

You may think that requirements are only for large projects. You’d be wrong. Requirements are important whatever the size of project.

One of the things that can kill a project is the feeling that it is never going to end. You’re working away hour after hour, day after day and don’t feel like you’re getting any closer to the finish line.

That is why requirements are so important. If you nail the requirement down early on, ideally before you’ve written any code, you will have a much better understanding of what you need to deliver.

You will also avoid the feeling of being lost.

If you have any ideas for enhancements during the project, document the requirement and schedule it into a future version of the project. Then return to implementing the first set of requirements.

Your requirements need to be quite specific. Vague requirements like “Implement X” is really of no use. Be very specific. Outline precisely what is to be implemented, what data is required with examples. The examples can then form the basis for your tests. The requirements should specify the very minimum you need.

Your first version does not have to be released, you can iterate over a number of releases before you release your project.

Tools Can Help

There are loads of web apps out there to help you organise a software project. Many implement a variant of the agile board.

If you have a team of people, then using some kind of agile board is a great idea. For one person teams I think they add a little too much ceremony. If you find yourself spending more time fiddling with your agile board than actually working, then you’re over complicating matters.

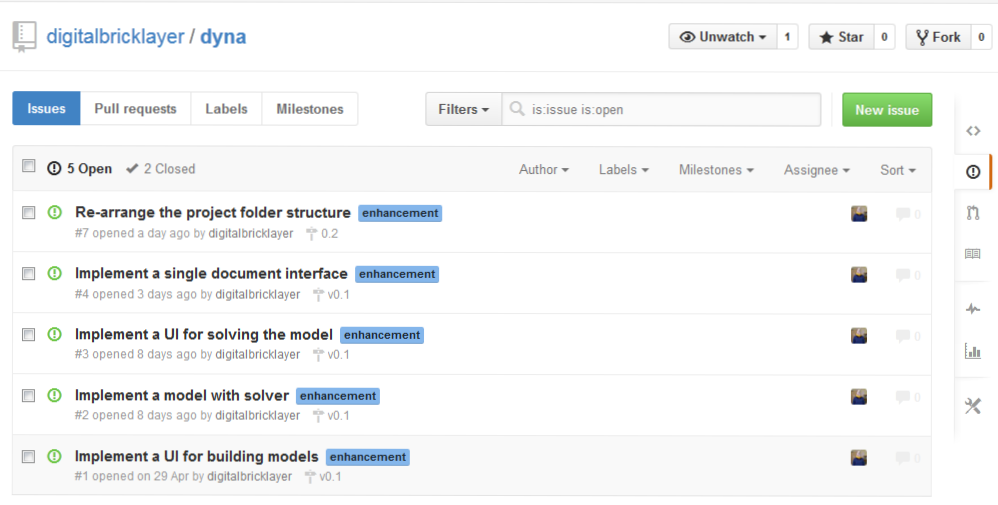

I’ve found the very minimal GitHub Issue tracker to be ideal. You can’t spend a long time configuring it because there’s very little to configure. You can create issues, label them and add your requirements in the issue text. You can organise your requirements into milestones. When you’ve completed all of the issues attached to a milestone, you’re done. Move on to the next milestone.

Dyna project issue tracker.

Make issues that take a small amount of time to complete. A single issue that takes many months to implement will prove hard to gauge progress. But, taking a large task and breaking it down into lots of smaller issues begins to give you some momentum. You’ll feel like you’re achieving something when you are continually marking issues as closed. If you feel like you’re making progress, then you’ll have momentum and are more likely to finish.

Realistic Expectations

Related to requirements. You need to be sure that what you are building can be built in a time scale you are comfortable with. You are one programmer, the project you take on needs to be doable in a reasonable amount of time. I’d say that one year is the very outside of what I could cope with as a lone project. If I can’t program the project at the very outside in one year, then I don’t take it on.

In addition, if the project requires resources you don’t have, then either you need to have a plan to get hold of those resources or don’t start the project. A vague I’ll sort that out sometime near the end of the project will likely just mean the project is never finished. Resources like graphic designers or UX people don’t just pop out of thin air. Wishful thinking won’t help.

Perfectionism

The temptation to create something perfect runs pretty deep in a lot of programmers. Perfectionism is very destructive because you can spend an inordinate amount of time ceaselessly tweaking something that, in the end, really isn’t very important. Worse, on lone projects, there is nobody to stop you disappearing down the perfectionism rabbit hole.

Every time you change something that already works you need to be questioning whether anybody will care about the change. Does the user really care about your obsessively edited product icon? The answer is almost always no. That is not to say that you need to put up with mediocrity. But, there is a big difference between excellence and perfection. Not understanding the difference between those two things causes an awful lot of projects to fail.

Getting Stuck

There aren’t many projects that you know how to implement every feature at the very beginning. At some point during the project you are going to be coding something that you don’t know how to implement.

Everybody gets stuck at some point. There are extra difficulties from getting stuck as a lone developer, not least that you don’t have any colleagues to bounce ideas off or to provide technical help.

How can you ensure that getting stuck does not kill your project?

You can ask questions on Q&A sites like Stack Overflow, but some questions don’t lend themselves to Q&A sites.

Let’s say you’ve exhausted the usual Q&A sites and you’re still stuck. What do you do now?

The simplest strategy is to isolate the problem. You need to focus solely on your problem, not worry about how you can integrate it into your project. You need to be able to try new ideas as quickly as possible without going to the trouble of fitting it into your existing code.

Most programmers end up with a disk full of small projects used to solve technical problems. A useful side effect is that they make asking good questions on Q&A sites a lot easier too.

If you have doubts about a particular technical area at the beginning of a project, it can help to tackle that right at the start. Then if you do get stuck you will at least be brimming full of enthusiasm and therefore be less likely to give up.

No Version Control

Version control systems give you a lot of benefits whether working on your own or not. The main benefit they give is the ability to experiment, and more importantly, go back to a state before the experiment started.

I remember a lot of projects when I first started programming, when source control was not commonly used by PC programmers, a lot of projects were destroyed by experiments gone bad. I’d have an idea for a change and then hours or days into the change I’d want to abandon the changes but couldn’t. Either I somehow got the project back to a position I wanted it to be, or I’d abandon it. There is nothing worse than getting into a change and knowing you can’t go back.

There are no excuses for not using source control now. There are loads of providers, most with free plans, and the tooling is great too. You don’t even have to learn the command line any more, Visual Studio and lots of other IDEs have source control tools baked right in.

Summary

It is easy to forget how much psychology comes into play whilst programming on your own. Momentum or the feeling that you are making progress is absolutely key. If you lose momentum, you are much more likely to give up.

Developing software is an intensely psychological activity. Developing software on your own doubly so.

Update 2015/07/13: Adds the “No Version Control” section.